On the Relevance of Aesthetics in Permaculture

(With the Special Mention of Five Techniques I Often Employ to Turn Heads)

Often as I contemplate how to make a garden more beautiful, thoughts I find myself having more and more, there is something within me that questions my inclination to do so. I feel like permaculture doesn’t really concern itself with beauty, at least not in a theoretical way. In reading a manual or the latest article, I rarely see any ideas put forth about how a garden design might look better.

However, the space for conflict between function and form made me remember Coach Hatch, a trainer of Olympic-style lifters (and Olympian competitors). Before training under him, all of my experience with weights had been geared towards body building. Upon hearing this, Coach explained that his system may inadvertently make me look athletic, but the goal was to gain strength, not be pretty. And, it did work out that way, but that was around twenty years ago.

The point is lifting, for Coach Hatch was of substance, like the underlying design in permaculture. I’d gone to him to better compete in the sports I played (eventually competing on his weightlifting team as well). His was the permaculture version of lifting, where using sound technique and building strength were much more important than bicep measurements. That my body turned sexy and muscular, much more so than a hulking body builder, well, that was just a bonus.

Actually, this is a very similar notion to what I’m thinking about with beautiful garden designs. The truth is that, as a serious weightlifter, I liked having an athletic body and now, as a permaculture designer, I like having a nice-looking garden. And, as long as the process isn’t sacrificed or forgotten, as long as the design is doing its work and providing a nice aesthetic, then I think it’s a good thing.

Why Aesthetics Counts in the Garden

To veer into our topic a little more pointedly, I’ve come to believe that aesthetics in the garden, especially those in the central zones, is of notable relevance. In the end, food can certainly grow without beautiful surroundings, but our involvement in the system will be much more likely if we create pleasant environments in which to dwell. If we want to be there, if we make sure being there is on the agenda, then the garden will get whatever attention it needs, much the same as—by design—putting a particularly needy bed near a well-trodden pavement.

As someone who often introduces people to permaculture, I also believe that showing them more classically garden-like, of course not with tilled rows but with borders and clean pathways, puts them more at ease with the idea. While we aren’t building our gardens to wow people with pathways so much as production, it does no harm to have both. If we build our gardens as places to spend time, then it should offer us great benefit as the observers and tenders of the plot.

For that matter, some degree of orderliness puts me more at ease. I like walking through the garden, knowing I’m not standing on a low thicket of herbs that’d be better suited for eating. I like being able to readily locate the type of plant that’s on tonight’s menu. In a relatively snake-laden part of the world, I also enjoy seeing where my feet are going to land. In other words, I’ve not raked those pathways for that aesthetics alone. It’s a task, like any good permaculture task, with multiple and practical functions. Plus, the debris goes to compost or mulching.

Permaculture—Like Competitive Weightlifters — Can Be Pretty

At no point in a permaculture manual have I read that our gardens shouldn’t be this way, but I think the overall impression sometimes given is that building beds with obvious aesthetic purposes in mind, sometimes even at the cost of planting space, is somehow a sin. Personally, I don’t always feel this way. I’m willing to sacrifice the growing space for a couple plants here and there if it makes the garden a more amiable home for humans, much the same as I’m willing to cut a trail through the jungle so as not to constantly become tangled in thorns, devoured by ticks, or lost in the thick.

That said, permaculture is different than what many farmers envision as a beautiful field. I’m not suddenly suggesting that straight, plowed rows of single crops planted in bare soil is what works best because it’s tidy. And, I’m not in favor a huge collection of purely ornamental plants, however beautiful, when other, more versatile and useful flora could be there instead. Nor would I like to suddenly stop replicating nature’s piles of leaves on the forest floor, utilization of water catching low spots in the landscape, or milieu of plants working on all different levels of the growing spectrum. Permaculture design is not on trial.

But, I believe that permaculture designs can also be pretty. No one is suggesting that we abandoned those large, festering piles of biomass that we accumulate and store. Of course not. Those are important. Nor is a densely stacked food forest not a thing of beauty in its own right. The idea is only that there is more to function that maximum output, minimal effort all the time. A garden, in the right hands, can be an absolutely work of art and highly productive, and for some people and places, both the aesthetic and the output is relevant.

Design Elements That Bridge the Gap

Because I tend to do new, simple, and small-scale demonstration gardens for people, things where they can see several techniques at work and interact, I tend to try to use the opportunities already intrinsic in the design to make it visually appealing as well. I still pile up organic material, dig swales, and mulch like mad, but I aim to do it all in a way that makes a functional garden flex its natural form as well. Here are some of the things I think about utilizing for both form and function:

The Silky Curve of Contour: It gets them every time. The overwhelming element of beautiful and functional permaculture design is that it feels so natural or, at the very least, in tune with nature. Planting and making swales on contour provides something so much more stimulating and sultry (That’s right: Sultry) than earth ripped up into straight lines. As a matter of fact, rarely do those cartoon images of row farms on cartons of milk or blocks of cheese not include at least some hills and texture to the landscape. For me, I try to accentuate those curves and hide the crass corners and incidents of synthetic straight lines.

The Tidiness of Well-Laid Mulch: Mulching is mandatory for me. It’s the advice I give nearly every person who asks me how they might make their garden function without chemicals and excessive watering. It’s how I go about slowly building soil, from day one of working on a bed. And, while at times that might involve a hulking, unsightly pile of material, I always take the time to spread it out nicely, to contain the mulch from spilling over onto pathways. The difference is extraordinary: An un-mulched bed cracks and dries out or erodes into muddy slicks, and an untidily mulched bed looks like a heap. I say chop and drop with flare.

Ponds and Open Catchment Systems: Who knows why it is that water is so appealing to look at in a landscape, be it suburban patio garden or a lakeshore, but what’s for sure is that using catchments for their function—increasing fertility or cleaning greywater or stopping erosion— as well as for their beautiful form, just makes sense. I like ponds overflowing into other ponds. I like swales winding their way through a space. I like rain gardens that fill during the deluge and slowly soak into the landscape afterwards. Most people do. The real need to catch water, and the fact that it’s a beautiful thing to see in motion, just works.

Nature’s Geometry at Play: While I try to soften the rigidness of most manmade structures (I do appreciate that squares, rectangles, and straight-sided figures are often easier to build), I also like to highlight the element of natural geometry in the garden. I love spirals, and even though herb spirals might not be necessary in the sense of growing herbs efficiently, I think they make a stunning and productive addition to a garden. As do untamed curved edges that capture extend that particular spot for plant and animals diversity, or a particularly beautiful chunk of wood atop the bed or a border along the side, or wayward vines to provide a rough awning.

Tended Paths and Garden Beds: As noted earlier, I’ve even managed to find viable reasons to tend my garden a little more than many would have, but it’s something that doesn’t feel like work to me. I don’t fret about removing every leaf from the pathway or each weed from the bed, but I find solace—much as I imagine the Zen garden works—in spending time keeping it functionally tidy and then more time admiring the result. Of course, this is relative to zone: A trail through the natural forest won’t get the same preening that the pathway from the kitchen to the lettuce patch gets, just as those trees won’t be “cultivated” as frequently as the arugula.

The Function and The Form

I’m not sure where my internal guilt over all of this arises. I’m not sure if I read something somewhere or if the simple practicality of a permaculture approach makes me feel that the effort put forth towards the aesthetic is wasted effort. But, I know that sometimes when I’m spending energy and hours putting a more attractive sheet of mulch over a rougher one—even when it isn’t functionally necessary—I question the value of it. In the end, though, the compulsion is just too much, and ultimately, that nicer looking sheet of mulch brings me to observe that bed more often. What’s more is that none of these forays are done at the expense of design but rather only as means of fully embracing it and illustrating the potential I see.

Lastly, I’d just like to note that the pull of an attractive garden to permaculture newbies is generally but the first step into a new understanding and appreciation of all the things and thoughts at play in a permaculture design. While that swale may look like an arbitrarily attractive curve at first, once an explanation is proffered, I find people are as interested or even more so in the underlying interactions below the surface. Additionally, the appreciation for and of nature in the design only furthers them to explore more, and for me, spreading the ethics of permaculture is high on my list of tasks to be accomplished within my practice.

Thus, without reservation, I do believe aesthetics, in whichever ways we personally choose to productively and constructively pursue them, are very relevant to permaculture design. And, while I don’t hold quite so much confidence in my muscular prowess as I did in younger days, Coach Hatch had recognized the something similar: He’d told me that my body wouldn’t be like a body builder’s but that a more natural, athletic body had its own aesthetic, and that it’s capabilities would definitely be more productive and purposeful (“explosive”, was the word he always used) with regards to sports.

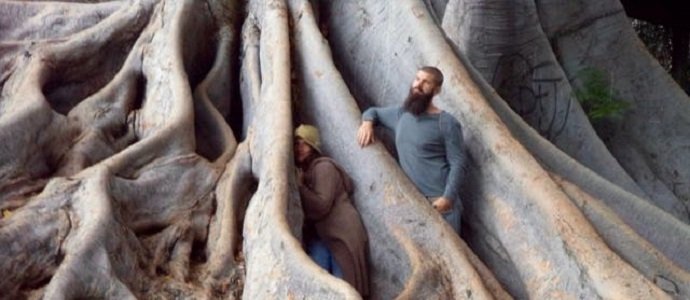

Feature Image – Hiding in Natural Beauty, Photo Courtesy of Emma Gallagher